Gibbs St. Pedestrian Bridge

Portland, Oregon, USA

Portland, Oregon, one of the greenest city in America, is renowned for lush hilly landscapes and a citizenry connected to one another and their environment. The mild climate and frequent, gentle, nourishing rain give people a keen appreciation of the water that trickles down the streets towards the Willamette, the river that divides the city in two.

Over 150 years Portland’s citizens proudly built a fleet of magnificent bridges tying the city together; connecting all citizenry to commerce and recreation.

The city’s array of bridges represents every spanning technology from towering suspension spans to intricate draw bridges. The bridges support all manner of transportation; pedestrians and bicycles are equally as important as railroads, buses and automobiles.

The 1960s brought Interstate Highway 5 (I-5), another river of sorts, to divide the city. At the time many neighborhoods were reconnected by bridges built over the highway. However, there was one important exception. The Lair Hill neighborhood, which originally supported the industrial waterfront, became severed from it. Since the 60s the South Waterfront’s industrial use faded. It stood mostly vacant until it was reborn in the 2000s as a residential and commercial zone. A dense neighborhood of high rise towers developed to enjoy proximity to the river, a streetcar connection to downtown and views of Oregon’s natural landmark Mt. Hood. Meanwhile, Lair Hill economically languished across the highway.

True to its character, Portland’s “green-street” corridors convert auto oriented hardscapes to shady pedestrian and bike friendly rambles that double as living stormwater treatment swales, connecting the community and the rain to the river. In 2007, the City designated Gibbs Street in the Lair Hill Neighborhood as one such corridor. The Gibbs Street corridor would contain a unique couplet of an aerial tram that connecting Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) to its offices and laboratories in the South Waterfront, and a bridge reconnecting Lair Hill back to the city, giving its residents renewed access to jobs and recreation at the riverfront and downtown.

The community’s shared ambition was to create a pedestrian and bicycle bridge spanning 700 feet over I-5. It must share the Gibbs Street alignment with the existing tram tower, meet an extremely tight $7 million construction budget, and minimize highway traffic disruption. It must also negotiate the steep topography and purify its own stormwater on-site.

Further, it must respond to two very different neighborhoods; Lair Hill is a quiet historic enclave of pleasant tree lined streets dotted with single family homes. In contrast, the South Waterfront is a bustling urban area marked by high rise glass condominiums, office and medical buildings.

A unique addition to a fleet of bridges-

Although 125,000 cars will pass beneath the Gibbs Street Bridge every day entering and leaving the city, the temptation was resisted to simply create an iconic gateway. The bridge is envisioned as a connection between southern Portland’s oldest and newest neighborhoods responding to its context by embodying the scale of each side while mending the rift that separates them. The bridge creates a uniquely Portland, pedestrian oriented sequence of varied experiences.

The west end of the bridge belongs to Lair Hill. Generous plantings mark the understated landing; a subtle continuation of the existing sidewalk. With a slight rise and a gentle curve to the north the experience changes. At the first pair of masts the experience becomes a realization of the rushing highway below and downtown Portland to the north. The diagonal masts cradle the bridge deck while suspension cables screen the bridge users from the raucous traffic.

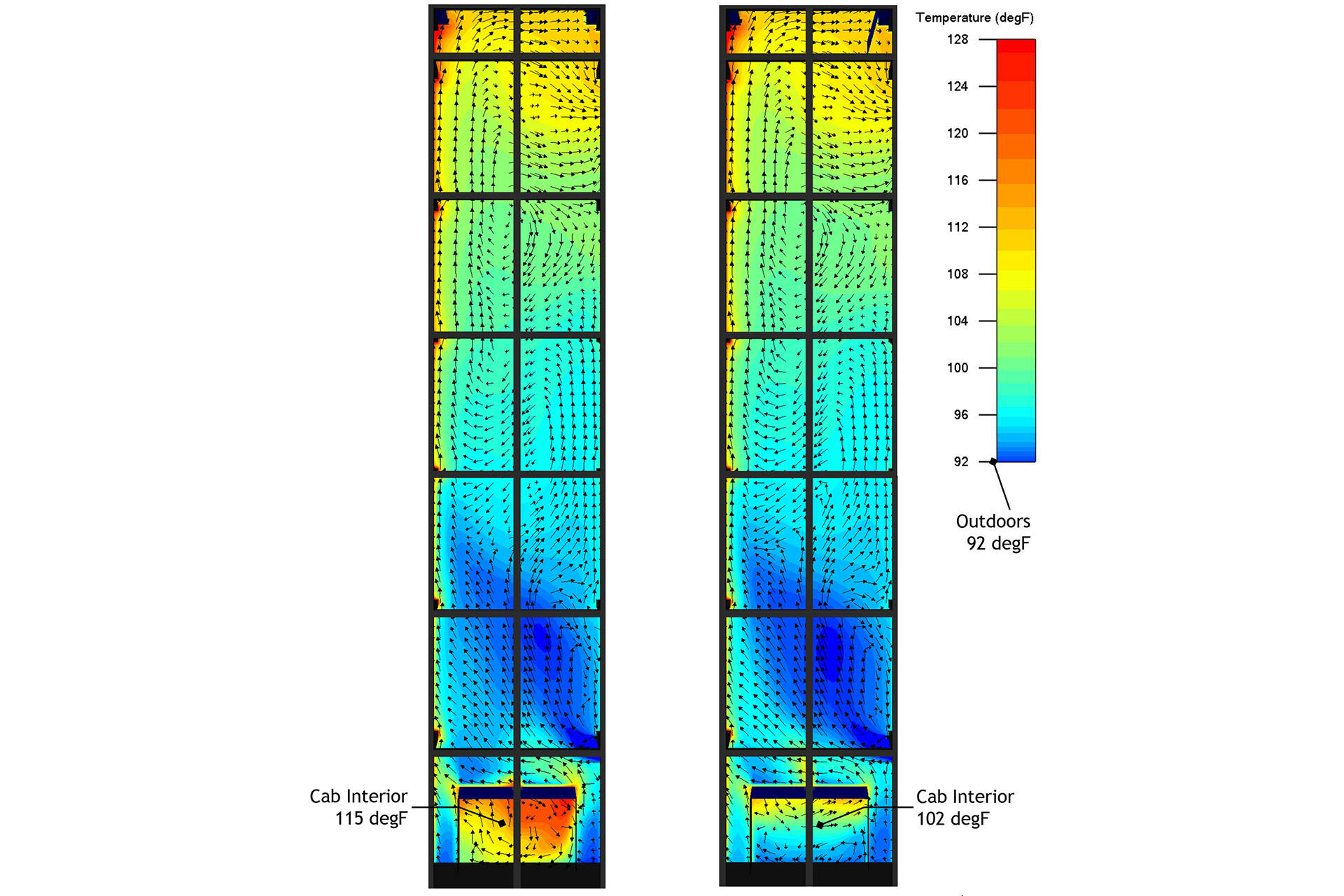

At the apex of the curve Mt. Hood slides into view between the second pair of masts. The east end of the bridge reaches out toward the mountain as a 60 foot high cantilevered observation platform, featuring a dramatic view of the Willamette valley and the thriving South Waterfront district. A unique twin elevator stands to the south side of the cantilever providing convenient access to grade without obstructing the view. The elevator’s shingled glass curtain wall allows natural ventilation while maintaining the transparency critical to public safety.

The next surprise is a generous stairway that scissors back upon itself, landing in the midst of a vertical garden. The garden is a series of bio-swales that collect and purify rain water from the bridge in successive terraces; one cascading into the next. The pedestrian path and stairs meander through the terraces to reach the plaza. Here bridge users can rest, enjoy the sound of the water, board the tram or streetcar, and access a future green promenade that continues to the banks of the river.

The bridge is a hybrid of box girder and suspension technology, designed to be the first “Extradosed” bridge in the United States.

This technology features lower mast heights than typical suspension bridges and is a highly efficient use of material; an economically responsible choice. The reclined angles of the cables also emphasize the horizontal nature of the bridge in counterpoint to the vertical tram tower. The bridge deck is comprised of identical modular precast concrete sections sculpted with integral curbs that channel traffic and water. Modular sections will be hoisted into place at night when highway traffic is minimal. Further accentuating the horizontality of the bridge at night, lights cast into the curbs create a simple illuminated plane without the use of light poles that would compete with the lines of the bridge cables. The concrete masts are also precast and identical in section, enabling incredible efficiency in material and erection. The masts are faceted with broad smooth surfaces, harmonizing with the chiseled form of the tram tower. The concrete rigorously expresses the compression elements while fine lines of stainless steel express the tension elements echoing the nature of the tram above.

The bridge mends a tear in an urban fabric, threading severed neighborhoods together once again. It is part of a particularly Portland composition; a crucial link in the green-street that enables Lair Hill to finally reach the river and complete the city again.

Drawings + CFD Modeling